I didn’t know who Ernest Hemingway was before I read his wonderful novel The Old Man and the Sea. Even when I first picked it up, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. I thought I had to read it because I had heard so many great things about it, and that was enough. However, after finishing it, I found myself genuinely moved.

The story, with its simple yet profound exploration of struggle and triumph, stayed with me long after I turned the last page. There was something deeply resonant about the quiet determination of Santiago, the old fisherman, that made me reflect on the nature of perseverance and success. So, naturally, I fell in love with Hemingway’s writing.

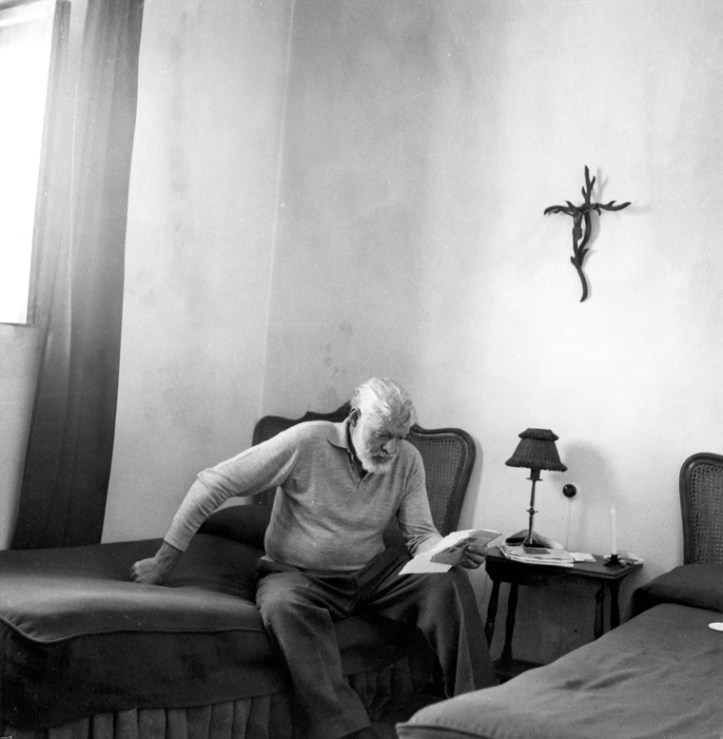

But as I dug deeper into Hemingway’s life, I realized that his personal story was a bit more complicated—and not in a way that made me feel the same warm admiration I had for his novel. Hemingway’s life was marked by intense highs and painful lows, including multiple marriages, troubled relationships, and a violent, often uncaring personality. In fact, the more I learned about his personal life, the more I began to question how a man who could write so beautifully about the human spirit could also display so much emotional volatility and reckless behavior.

Hemingway was a man of extremes. On one hand, he was brilliant, creative, and full of life. On the other hand, he was deeply troubled, prone to dark moods, and often seemed to push away the people who cared about him most. I mean, let’s not even get into his four marriages and various affairs. It’s almost as if he was determined to live out every possible version of the tortured artist cliché.

His relationships with women were far from perfect. His first wife, Hadley Richardson, was an understanding partner, but Hemingway’s infidelity caused a rift between them. His second marriage to Pauline Pfeiffer, an ambitious woman in her own right, ended in bitterness. His third marriage to Martha Gellhorn was marked by both personal and professional challenges, and his fourth marriage to Mary Welsh was no less complicated. Through it all, Hemingway’s attitude towards women and commitment seemed to reflect his overall emotional instability, his need for validation, and perhaps an underlying fear of being truly understood.

But what about the man behind the public persona? What did he hide behind the bullfighting and the war journalism, behind the drinking and the bold, sometimes exaggerated display of confidence meant to impress others? Hemingway struggled with his own demons.

His mental health was fragile, and this was worsened by the physical and psychological trauma he experienced during World War I, World War II, and the Spanish Civil War. Hi declining health, both physical and mental, led to bouts of depression, paranoia, and, ultimately, suicide. He wasn’t the rugged, larger-than-life figure he appeared to be. He was a man deeply affected by his own inner turmoil.

This complexity is where the Five-Factor Model (FFM) of personality comes in. The FFM helps us understand people by breaking down their personalities into five broad traits: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness [1]. Applying this model to Hemingway, we can start to make sense of his contradictions.

First, let’s talk about neuroticism. This trait refers to someone’s tendency to experience negative emotions like anxiety, anger, and self-doubt [2]. Hemingway’s emotional instability was clear, especially in his relationships and his personal struggles with mental health. His volatile behavior, including his eventual suicide, shows just how deeply these negative emotions affected him.

Next, extraversion. Early in his life, Hemingway was social and energetic [3], always seeking adventure. He was the life of the party, the bold adventurer, a man who thrived in the company of others. But as he aged, his extraversion diminished, likely due to his declining mental and physical health. His later years were marked by introversion, paranoia, and a retreat into his own mind.

On to openness—Hemingway definitely scores high here. His creativity, curiosity, and willingness to embrace new experiences are what made him such a master of the written word. He was unafraid to explore unconventional ideas and places [4], whether it was through his writing or his real-life adventures.

Agreeableness? [5] Well, Hemingway didn’t exactly excel in this area. He was often abrasive, difficult, and competitive. He didn’t go out of his way to please others, and many of his friends and wives described him as selfish and uncooperative. His personality was more about asserting himself than compromising with those around him.

Finally, conscientiousness. Hemingway didn’t score high here either. He lived a reckless lifestyle—drinking heavily, pursuing dangerous adventures, and treating his relationships with little regard for long-term commitment or responsibility. His lack of discipline and care in these areas contributed to his personal decline.

Looking at Hemingway through the lens of the Five-Factor Model helps explain some of the behaviors that made his life so turbulent. But what about the biological factors that shaped him? It’s well-known that Hemingway’s family had a history of mental illness and suicide.

Given that a biological approach in understanding personality differences focuses on how personality is shaped and influenced by genes, brain structure, neurobiology, gender differences, and aging [6], I believe it is a fitting framework to explore a personality like Hemingway’s. It suggests that our inherited traits and physiology can be used to understand human personalities [7].

Hemingway and his mother, Grace, did not have a good relationship. He even accused her of being the reason behind his father’s suicide. She was controlling and selfish. These traits were also used to describe Hemingway’s behavior by his friends and wives, which led me to suggest that he may have inherited her temperament, which refers to how individuals are different in their reactivity and self-regulation [8].

Since temperament is considered the biological groundwork shaping personality [9], both Hemingway’s and his mother’s difficult temperaments might be also the reason behind his constant conflicts with her, ever since he was a teenager, as noticed by those who knew him.

Another remarkable part of Hemingway’s life is how his family members are productive and smart. Hemingway used to get good grades at school and became a great writer. His brother, Leicester, was an accomplished writer as well. His sons Jack and Patrick have been recognized for their work as conservationists and authors, his daughter, Gloria (born Gregory) is a successful physician, his granddaughter Margaux was supermodel and actress, and his granddaughter, Mariel, is an Academy Award and Golden Globe nominated actress and author. It seems that creativity and intelligence run in his family. Intelligence is crucial for creativity, and personality factors are more predictive of creativity achievements [10]

However, this creative and intelligent family have been plagued with mental illnesses. His father, his sister Ursula, his brother Leicester, and his granddaughter Margaux, all took their own lives. People who lived with Hemingway reported that, prior to his suicide, his behavior was similar to that of his father’s in his last years.

His father was possibly affected by hereditary hemochromatosis, a condition in which excess iron build up in the body tissues and cause physical and mental decline [11] and may contribute to triggering bipolar [12]. It is known to be a genetic disease [13], and Hemingway was diagnosed with this condition, in the beginning of 1961, the same year he committed suicide. This suggests that he may have inherited some of his father’s psychological vulnerabilities that ultimately led to his tragic end.

Hemingway also suffered from physical wounds and traumas during his work as a war journalist in. He ended up with wounds in his head, and traumatic brain injuries can be one of the factors that contributed to some changes in his mood and personality [14].

Before wrapping up this psychobiography of one of my favorite writers, I have to admit that I liked Hemingway more before I learned about his many marriages, complicated relationships, and often aggressive, indifferent personality. His troubled nature and lack of empathy make his life seem more like a cautionary tale than a heroic saga. But despite it all, I can’t deny his genius or the raw power of his writing. The Old Man and the Sea is still a beautiful tribute to human strength, even if the man behind the words wasn’t as steady as his protagonist.

Enjoyed the read? Go on and buy me a chamomile 😋

References

(Scientific References)

- Widiger, T. A., & Crego, C. (2019). The Five Factor Model of personality structure: an update. World Psychiatry, 18(3), 271–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20658.

- Chmielewski, M. S., & Morgan, T. A. (2013). Five-factor model of personality. In M. D. Gellman & J. R. Turner (Eds.), Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine (pp. 771–772). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_1226

- Goldberg, L. R. (1993). The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist, 48(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.48.1.26

- John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative big-five trait taxonomy history, measurement, and conceptual issues. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality Theory and research (pp. 114-158). New York, NY Guilford Press. – References – Scientific Research Publishing. (n.d.). https://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers?ReferenceID=1015930

- Digman, J. M. (1990). Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology, 41, 417–440. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.41.020190.002221

- Canli, T. (Ed.). (2006). Biology of personality and individual differences. The Guilford Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-04115-000

- Burger, J. (2008). Personality (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thompson Higher Education. https://archive.org/details/personality0000burg

- Gartstein, M. A., Kirchhoff, C. M., & Lowe, M. E. (2024). Individual differences in temperament: A developmental perspective. In M. Zentner & R. Shiner (Eds.), Handbook of temperament (2nd ed., pp. 31–48). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-48627-2_3

- Rothbart, M. K., Ahadi, S. A., & Evans, D. E. (2000). Temperament and personality: Origins and outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(1), 122–135. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.1.122

- Jauk, E., Benedek, M., Dunst, B., & Neubauer, A. C. (2013). The relationship between intelligence and creativity: New support for the threshold hypothesis by means of empirical breakpoint detection. Intelligence, 41(4), 212–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2013.03.003

- Brown, S., & Torrens, L. A. (2012). Ironing out the rough spots – cognitive impairment in haemochromatosis. BMJ Case Reports, 2012(jul02 1), bcr0320126147. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr.03.2012.6147.

- Serata, D., Del Casale, A., Rapinesi, C., Mancinelli, I., Pompili, P., Kotzalidis, G. D., Aimati, L., Savoja, V., Sani, G., Simmaco, M., Tatarelli, R., & Girardi, P. (2011). Hemochromatosis-induced bipolar disorder: a case report. General Hospital Psychiatry, 34(1), 101.e1-101.e3. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S016383431100138.

- Beaton, M. D., & Adams, P. C. (2007b). The myths and realities of hemochromatosis. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology, 21(2), 101–104. https://doi.org/10.1155/2007/619401.

- Gracia-Garcia, P., Mielke, M. M., Rosenberg, P., Bergey, A., & Rao, V. (2011a). Personality changes in brain injury. Journal of Neuropsychiatry, 23(2), E14. https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.23.2.jnpe14.

(Non-Scientific, for Hemingway’s biography)

Ash, J. (2023, May 5). Ernest Hemingway’s Philosophy: Themes & Concepts. Literature Analysis. https://www.englishliterature.info/2022/02/ernest-hemingways-philosophy-theme.html.

Biography. (n.d.). https://www.ernesthemingway.org/p/biography.html

Farooq, A. (2017). Writing style of Ernest Hemingway. Uol. https://www.academia.edu/33353929/Writing_style_of_Ernest_Hemingway.

Hawkins, J. (2022, May 4). Tragic details about the Hemingway family. Grunge. https://www.grunge.com/852900/tragic-details-about-the-hemingway-family/.

Hemingway, M. (ca. 1959). Ernest Hemingway reading a letter at La Consula, the Davis estate near Malaga, Spain [Photograph]. Ernest Hemingway Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. https://www.jfklibrary.org/archives/ernest-hemingway-collection/hemingway-media-galleries/spain-1953-1960.

How mental health struggles wrote Ernest Hemingway’s final chapter. (2020, July 21). PBS News. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/how-mental-health-struggles-wrote-ernest-hemingways-final-chapter.

Kert, B. (1983). The Hemingway women: Those who loved him — The wives and others. W. W. Norton & Company.

Kraft, C. (2017, April 5). Hemingway’s Suicide Gun. Garden & Gun. https://gardenandgun.com/articles/hemingways-suicide-gun/.

Malik, I. (2024, November 19). Hemingway’s Depression: The untold story behind ’The Old Man and the Sea. Our Mental Health. https://www.ourmental.health/stars-struggles/hemingways-hidden-struggles-depression-behind-the-old-man-and-the-sea.

Moddelmog, D. A., & Del Gizzo, S. (2012). Ernest Hemingway in context. In Cambridge University Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511862458.

Vaynshteyn, G., & Vaynshteyn, G. (2021, May 4). THE HeMINgWaY FAMILY DeAths: Hemingway’s daughter thinks family is cursed. Distractify. https://www.distractify.com/p/hemingway-family-deaths.

Young, & Philip. (2025, February 14). Ernest Hemingway | Biography, Books, Death, & Facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ernest-Hemingway.